DRAGON SKIN

The wrinkled sea shining in the damp silvery dawn made me think of dragons’ skin and old Norse gods as the ship glided slowly into the harbor at Torshavn. The sun pierced dark clouds to illuminate buildings and harbor.

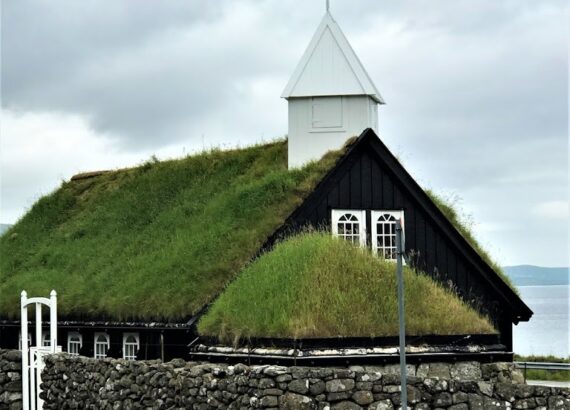

Torshavn is the capital of the Faroe Islands, a self-governing country within the Kingdom of Denmark (which also includes Greenland). A collection of eighteen islands rising abruptly out of the North Sea in the middle of a stormy triangle made up of Norway, Iceland, and Scotland, it’s low in population but high on atmosphere with mists, waterfalls spilling down the cliffs, sheep in green pastures, and sod-roofed homes. Although Celtic monks arrived in the 600s, it was the Norsemen in their dragon-prowed long ships who settled the country around AD 825. The inhabitants have made their living mostly from fishing ever since. And everywhere there are monuments to the enormous death toll arising from venturing into the treacherous waters.

I’d enjoyed a previous visit to the Faroes and was delighted to take another look at Torshavn (Thor’s Harbor) and to explore a different area of the country—this time concentrating on the largest island, Streymoy, where Torshavn is located.

The capital is a combination of modern glass-sided buildings, and sturdy old sod-roofed houses jumbled together, some dating from the 1500s.

It was obvious that beyond fishing, the tourism industry is growing rapidly, with birdwatchers, hikers, and other adventure tourists. Several four- and five-star hotels are under construction in Torshavn, and for those who want the very best and can afford to pay, there is a Michelin two-starred restaurant, KOKS, on the nearby island of Vagar serving such traditional foods as fermented lamb, wind-dried and air-salted, along with high-concept presentations of bounty from the sea.

Tradition is much in evidence. I strolled through the oldest part of town, stopping to watch a man in old-style clothing re-sod his roof while his helper clad modern safety-orange helped lift the heavy squares of dirt and grass.

The Faroese language is a variant of Old Norse and, judging by the music stores and ads for performances, very much a living language. With the exception of Viking heavy metal, most of the music videos I’ve watched seem melancholy and feature the weather. Besides the music stores, the main shopping area has a shop with traditional clothing, a bookstore with books in Faroese, and sweater shops common to all Scandinavian countries for good reason. With a cool, wet, and windy climate combined with a long dark winter, knitting is a natural pastime although the islands’ sheep are grown only for meat, the wool unsuitable for craft work.

The landscape on our way north was mystical in keeping with the ancient myths. Clouds rose and fell, fields of grass bent in the breeze, showers fed the eternal waterfalls, sheep grazed, orange-billed Oystercatchers poked along the fjord shorelines.

Village churches and farmhouses with their wild-flower-covered roofs looked as if they had always been there.

But when I turned my attention to the present, it was easy to see what a wealthy country it is. The houses are perfectly kept, the cars are new, the roads are perfect and the closer islands are connected by bridges or underwater tunnels. The infrastructure is paid for with high income taxes like other Scandinavian countries. The people I talked to were happy with the arrangement. With good infrastructure, free schools, medical care and old-age support, they said they got their money’s worth.

The end of the journey was the settlement of Saksun, in an enchanted valley with a lacy waterfall spilling down a slope, an old barn built of stone, and a sod-roofed church facing the fjord.

In keeping with the atmosphere, I visited a nearby farmhouse, abandoned at the beginning of the 20thcentury and now a museum. The main building of stone and wood was constructed around 1820, although an older building once occupied the space. Within its thick walls was a smoke-room, cow-barn, henhouse, potato shed, as well as the living quarters where the occupants raised their family, sheltered the village priest when he passed by, ate their simple meals out of wooden bowls balanced on their laps, and no doubt, watched their children suffer with no medical care. How hard it must have been in the isolated spot when the long summer days turned to long dark winters.

As I enjoyed coffee and home-made waffles in the tiny kitchen flooded with summer sunlight, I couldn’t help but wonder if the family told stories of the old times when dragons appeared in swirling mist shrouding the farmstead. Then, after the cows in the stall were settled and evening prayers were done, the wick on the oil lantern was trimmed and the family slipped into beds built into niches to await another day of toil.

All photographs copyright Judith Works