Woody Guthrie’s famous song written in 1941 to extoll the virtues of dam building on the Columbia River and its tributaries is not the subject of this story although the effect of all that damn dam building (some eighty) is one of the causes of the demise of the salmon fishing and canning industry that once powered the booming economy of historic Astoria Oregon.

The small city sits a few miles from the mouth of the Columbia where the river empties into the Pacific Ocean in a roiling combination of swift and silty fresh water fighting the ocean tides and storms. The result is treacherous ever-shifting sandbars and forty-foot waves. Some two hundred large ships have been recorded as sunk and many lives lost in this area rightly called the graveyard of the Pacific. Some years ago, my coworker and her husband drowned on an ill-fated fishing expedition when their small boat overturned in the heaving swells.

The Lewis & Clark expedition spent the winter of 1805 – 06 at a nearby spot they named Fort Clatsop before they began their long return trek to St. Louis to report to President Jefferson who commissioned them to find a route to open up the far West. The weather was rotten. Clark summed up the situation: “O! How disagreeable is our Situation dureing this dreadful weather.”

The town itself began in 1811 as a fur trading outpost backed by John Jacob Astor under British Control until 1846 when the area became firmly under US control and settlers coming over the Oregon Trail came to exploit fishing, farming and timbering no matter what the weather —67 inches of rain or more plus windstorms blowing in from the Pacific every year.

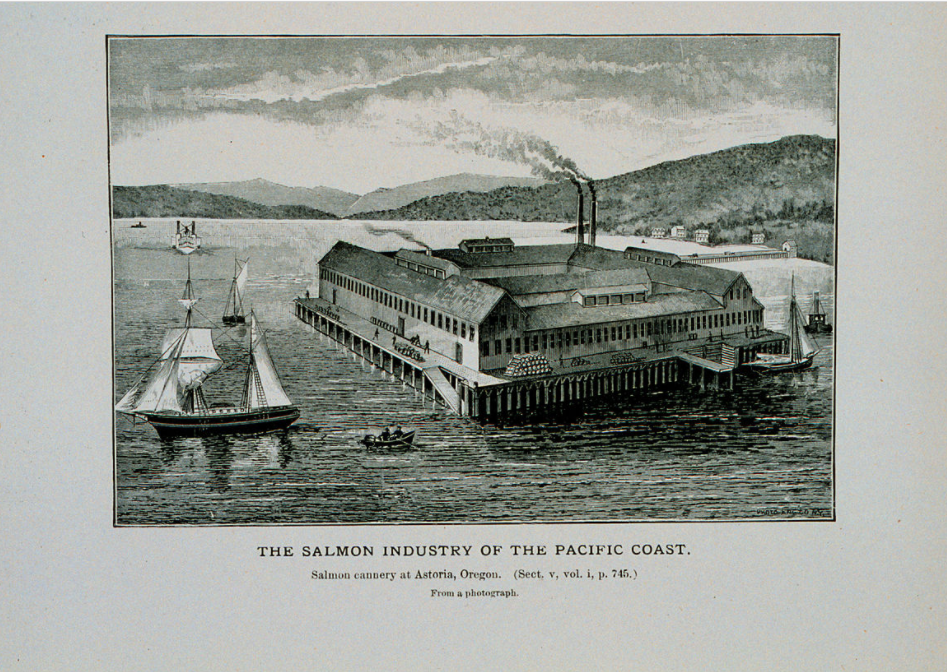

Bursting with immigrants, most of whom were Swedish, Finnish, or Chinese, the town was a Wild West in the glory days of canneries and lumber mills fed by endless fish and logs. Now it is more famous for tourism and the canneries are memorialized on the downtown trash containers.

The city hosts an annual poetry festival for Fisher Poets, microbreweries abound and the occasional cruise ship stops by.

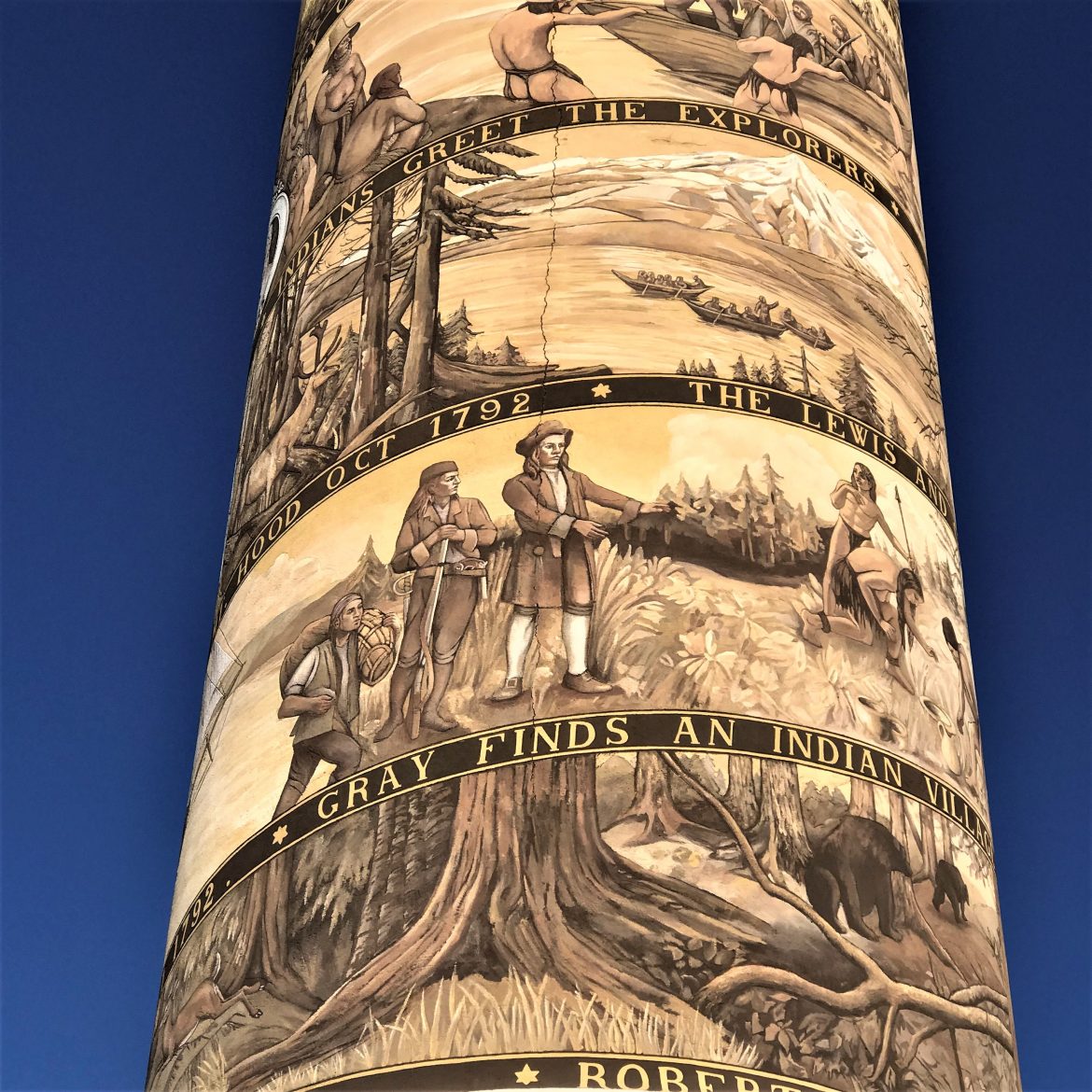

The most prominent attraction is the Astoria Column, a 125-foot-high tower inaugurated in 1926 to highlight the early history of the area from Native American life to the coming of the railroad in 1893. The tower is interesting artistically even if not always correct (the native peoples didn’t erect totem poles and Lewis & Clark arrived in boats not dugouts). The setting, the highest hill in the city, is incomparable presiding over the city, the river, and the countryside especially on a sunny day.

The painter, Attilio Pusterla, was an Italian American who used the same spiral story-telling method as that carved on Trajan’s column in Rome, although he used an ancient technique called sgraffito where a lighter color of plaster or other substance is applied over a darker one and then the design is incised. The result on the Column is the unwinding of a story in mellow shades of beige and brown that harmonize with the setting.

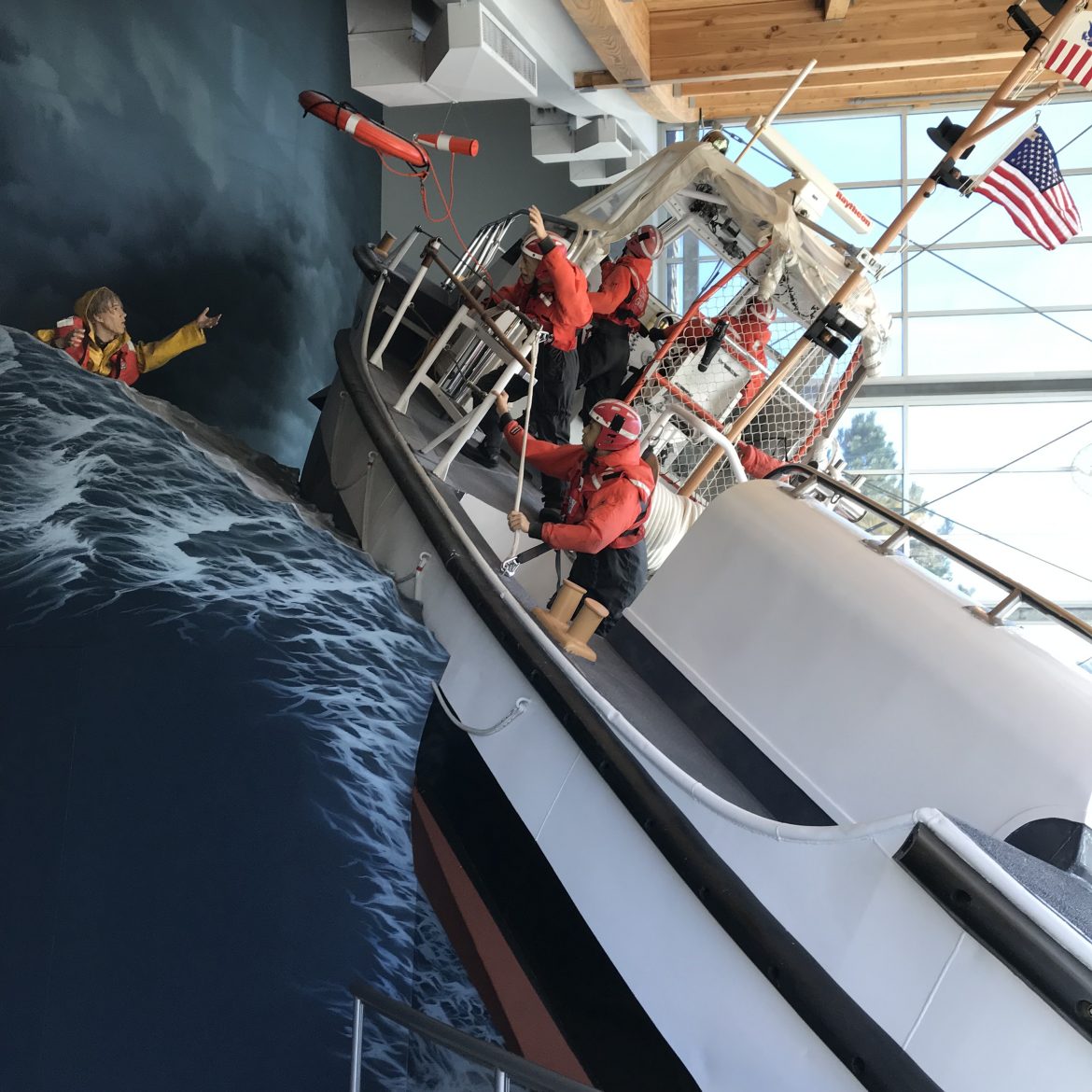

The Columbia River Maritime Museum surely is in the first rank of American natural history museums. Room after room tell the story of the mouth of the 1200-mile great river from maps and charts of the earliest explorers, crossing the bar, the fishing and canning industry, fishing vessels, and the Coast Guard’s heroic rescue operations.

An old ship once used as a lighthouse is anchored nearby.

The freighters slide by, some having passed successfully over the treacherous bar to go upriver, and others ploughing ahead as a pilot ship speeds toward them so the pilot can jump onto the dangling rope ladder to ascend to the bridge and guide the ship toward the ocean and its onward journey.

We crossed the river on the four-mile-long bridge opened in 1966 to mark the final connection for the Pacific Coast Highway running from Olympia, WA to Los Angeles. Our goal was Cape Disappointment on the north side of the river where there are spectacular views and two lighthouses. Cape Disappointment was already named by the time Lewis & Clark reached the site in November 1805. The Spanish explorer Bruno Heceta, named it “Bahia de La Asuncion,” or Bay of the Assumption in 1775. Then in 1788, British trader John Meares named it “Cape Disappointment” when he mistakenly believed that the mouth of the Columbia River was only a bay. He missed the riches of the river.

The lighthouse, looking weathered, sits just inside the mouth of the river.

To access it we hiked a short but steep and rough 1.2 miles puffing our way past the Coast Guard station famous for daring rescues in perilous storm conditions.

The lighthouse sits near a mysterious sign, one that I assume is for navigation although I’ve not been able to determine the meaning.

The second lighthouse is North Head, neat and tidy and reachable by a paved path. On this glorious sunny day, it was hard to imagine desperate sailors trying to pick it out as waves and wind lashed the ship and they feared for their lives. We only had to walk to our car.

If you are interested in the history of this area, I recommend Karl Marentes’ saga Deep River about logging, fishing, and labor unrest roiling Astoria and the lands just north of the river in the early 20th Century.

All photos copyright Judith Works except that of the salmon cannery public domain from NOAA

A wonderful place! Looking forward to a future visit.

I’ve only had lunch there while passing through a few years ago. I love that tower and would like to explore Astoria more thoroughly now. Thanks, Judith!

As excellent article, Judith. It’s a fascinating place with its natural beauty and its history of explorers, ship wrecks, and salmon canneries. I’m glad you took some closeups of the tower.

I remember learning about Astoria and John Jacob Astor when I was in 9th grade, but I’ve never been there. Our family stayed for a few days in the Cape Disappointment Lighthouse rentals one summer, but we didn’t cross over to Astoria.

We were very (very) fortunate with the weather.