A first stop to contemplate that medieval world on a day out of London was Salisbury Cathedral. Some 90 miles west of London, the cathedral is most famous for its ever-so-slightly skewed spire, at 404 feet, the tallest in Great Britain. The cathedral sits in the middle of an immense greensward in the middle of the town of the same name. Because of its easy access from London and nearness to Stonehenge, it has a heavy influx of tourists.

As we approached the entrance, the magnitude of the attraction was evident with lines of tour buses in a parking lot disgorging passengers. We joined the crowd to enter a medieval world from floor to vaulting.

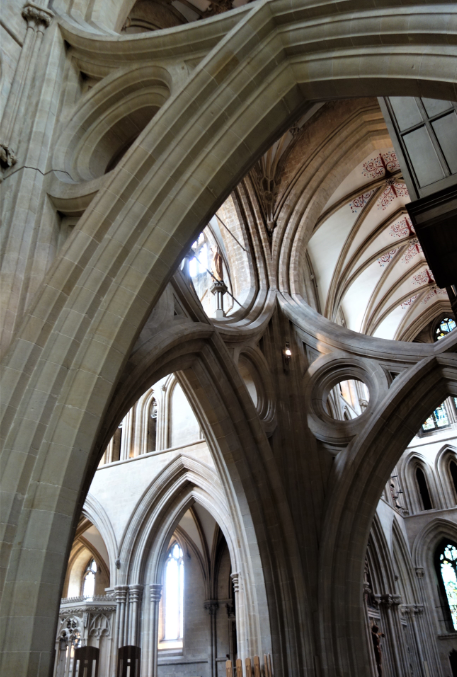

The foundation stone was laid in 1220 and consecrated in 1258 but the cathedral isn’t far from the ruins of an Iron Age settlement, later Roman fort and then a Norman town known as Old Sarum where an earlier cathedral once stood. The stones of that cathedral were used to build an English Gothic architectural wonder where we stood among the others gazing upward at the vaulting supporting the building. Most extraordinary are the curving scissors arches leaping into the air where the nave and arms meet to form the traditional shape of a cross. The mason, Master Nicholas of Ely, who designed and oversaw the workers didn’t need computer programs – his architectural vision and skill was in his brilliant mind and hands.

The discussion over a sandwich of crusty country bread filled with cheddar and diving Wiltshire ham washed down with local ale, centered on what to see next. Stonehenge is jammed, Avebury sounded interesting, but where I’d long to go for years was Wells. Our driver blanched when he thought I said Wales but after convincing him that wasn’t the case, we headed cross country to the small town set in the rolling Mendip hills deep in Somerset. And there I found my transcendent experience: The thin space where sacred and profane meet.

The small town of Wells is without railroad or freeway connections and therefore lacks day-trippers. It exudes a sense of peace because the center of life is the magnificent Gothic cathedral. The first known settlement was around a holy well in Late Roman times: 400 – 600 AD, a time when the Roman Empire had collapsed and England was a conglomeration of small Saxon kingdoms. The King of Wessex gave land for a church to a bishop in 705. The small church became a cathedral in 909. The foundation for the current masterpiece, the first Gothic-style church with its pointed arches and abundance of stained-glass windows in England, was laid in 1175 but the building wasn’t completed until 1508, a testament to the power of faith to persevere.

Visitors were few and quiet allowing us to wander at will and to contemplate the structure in a hushed atmosphere. Time stood still, or even ran backward. The entrance to the nave made me think that the ribbing on the ceiling was like looking into the insides of a fish or whale—a view Jonah might have seen. But again, it was the scissors arches that captured my awe. How could have William Joy, the master mason in 1338, known that to brace the central tower he needed to build magnificent swoops of stone on three sides of each of the four pillars? They were a divine inspiration.

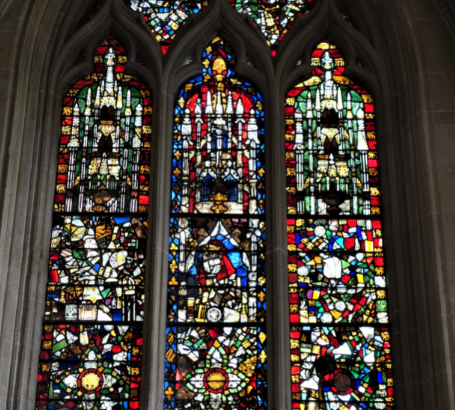

Time slowed as we wandered the vast space, contemplating the beautiful Nave, Lady Chapel, Cloisters, and the substantial area behind the main altar called the Quire and Retroquire. The lower part of the beautiful windows are a simple jumble of glass – the remnants of the biblical scenes smashed in a time of religious strife in the 17th century.

But we returned repeatedly to the arches to wonder at their perfection and to imagine the candle-lit processions with Choristers chanting and singing as they still do.

All was silent as I imagined Evensong in my mind’s eye.

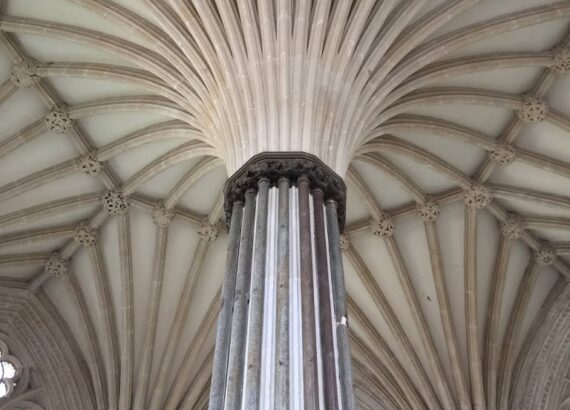

Around the sides are seats where the Canons, who managed the church and its business affairs, sat under their name; their assistants, the Vicars, sat at their feet. In the center of the room is a pillar with 32 vaulted ribs springing from it as if it were a fountain.

The windows are mostly clear glass as the originals were smashed in the 17thcentury as they had been in the main church. We crept carefully down the stairs that that resembled a gush of cascading water imagining how many Canons and Vicars must have lost their balance and fallen to their deaths as they descended in flickering candlelight.

We paused for reflection in an ancient graveyard

before strolling in the lovely quintessentially English Vicar’s Close, a stone-paved street connected to the church by an overpass called the Chain Bridge. The street is lined with about twenty lovely homes and gardens, originally built in 1348, and still occupied by fortunate cathedral staff such as the Organist and choir master. Although I have no doubt the interiors of the homes are modern and have high-speed internet, the exterior of the Close is an English dream encapsulating everything magical about English villages.

Too soon, it was time to leave.

We headed east back to London, stopping along the way to allow a herd of cows heading for their own barn. Traffic stops at milking time in the countryside. But as we approached London the present day took over and the conversation returned to the subject on everyone’s mind: Brexit and what the future held.

Constable painting from Wikipedia, pubic domain