One of the major reasons to visit Norway is to see the magnificent fjords, sea arms that stretch far into the landscape. One of the most spectacular is Lysefjorden, not far from Stravanger, a city between Bergen and Oslo, the capital. The 26-mile long fjord with waters 1600 feet deep is hemmed in by cliffs rising to 3000 feet. It’s no wonder that Victor Hugo used it as a setting in his 1886 novel, Toilers of the Sea, where he wrote that “Lyse-Fjord is the most terrible of all the gut rocks of the ocean.”

Our visit was far more mundane—it’s not every day that one finds three domestic goats on a almost vertical rocky hillside with no visible farm buildings. How they got to this remote spot on the fjord and where they went during the fierce winter will always be a mystery to me. (Helicopter?) Nevertheless, they appeared to be having a great summer holiday. One was all milk chocolate colored, another milk white with a chocolate head, and the last one looked as though the front half had been dipped in chocolate.

The captain slowed the engine and a crew member lowered a ramp. She then picked up a bag of bread and walked to the goats who pushed and shoved to get the snack as we, the passengers clustered to take photos. Payment to their participation in the photo-op finished, the goats returned to their rocky perch and we continued up the narrow sea-arm to view waterfalls, villages, pirates’ hideouts, and the famous Pulpit Rock rising straight up 1982 feet from the saltwater. Along with serving as a spectacular viewpoint for hikers, the rock is used for BASE jumping—a terrifying thought.

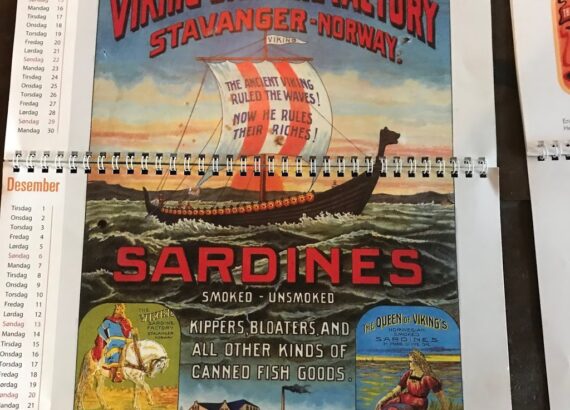

The city of Stavanger makes its living from provisioning the North Sea’s oil drilling industry, and like everywhere scenic, tourists. We skipped the architecturally-innovative oil museum in favor of a museum honoring another ocean resource: sardines. The canning industry, with 70 processing plants in use from about 1880 to the mid-1950s, has long passed its heyday but the museum was one of the cleverest we’ve visited: installed in the old and nicely-named Venus Cannery, it takes a visitor through the process complete with movies from around World War One.

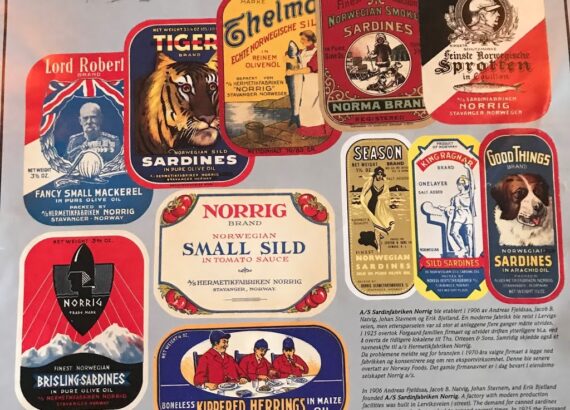

The machinery to make and seal cans still functions and the tin samples of fish sizes are laid out to show how the workers learned to sort. The office with its old typewriter stands ready to send out another invoice to somewhere in the world as demonstrated by the display of sardine can labels.

We arrived on a day when the smoking ovens with low-burning fires were lit over rows of sardines. The man tending the fire handed me one of the fish. Delicious!

Of course, there’s a gift shop. We filled a shopping bag with a couple of cans of King Oscar sardines, and an apron now in use by my chef —aka husband. It’s not everywhere that one’s chef wears an apron with a sardine can emblazoned on the front.

It was pleasant to stroll the old town where flowers flourish in the long summer days, before a visit to the cathedral, a Romanesque structure dating from 1125 later remodeled with Gothic touches.

The cathedral is the largest cathedral in Norway. The stained-glass windows had been removed for restoration but we were fascinated by the unusual plaques apparently commissioned to honor the stiffly-starched pious and wealthy 17thcentury families associated with the church. The ruff on one woman looked like a crumb-catcher although I couldn’t see how she would actually have been able to eat.

The severity of the sober families was a complete contrast to the wildly-colored pulpit with primary-colored Biblical scenes in folk-art styles.

After, we browsed a small open market, considered whether we should buy a reindeer pelt, an inevitable troll, or sample unusual food choices before settling for a local Norwegian beer, comparing the feet on the glass to our own tired toes.

All photos copyright Judith Works