I met a traveler from an antique land.

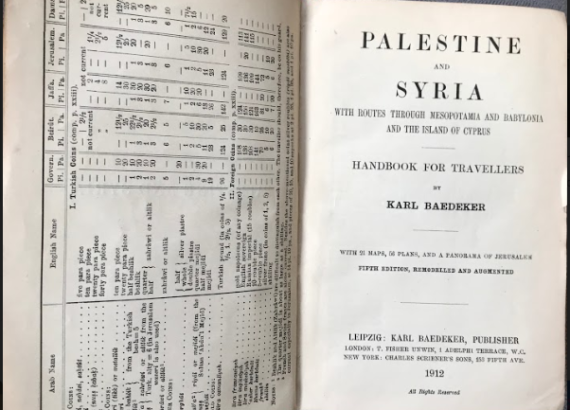

To be honest, I didn’t actually meet anyone in person but through the 1912 edition of Baedeker’s Palestine and Syria travel guide, a wonderful Christmas gift. I love old guides that reveal so much about conditions as seen through the eyes of whomever contributed to the text and what they thought would be important to the inexperienced traveler who had a case of wanderlust.

The red-covered Baedekers were known to be reliable and the traveler wouldn’t want to be without one – remember Lucy Honeychurch who was lost in Santa Croce without her Baedeker in “Room with a View”? I do have the very one Lucy carried (or at least a copy of Central Italy which covers Florence and Rome). Both guides were bought from the well-named Insatiables bookstore in Port Townsend, WA.

According to the flyleaf for the Palestine and Syria book, my fellow traveler was someone named D.P. Wetherald. I don’t know if it was a he or one of the intrepid British women like Gertrude Bell who tramped all over the area before World War I and drew the boundaries of the countries in the Middle East after the war. Whoever it was, bought the book in Cairo on March 7, 1914, just six months before the world turned upside down and the subsequent fall of the Ottoman empire that ruled the area. The guide covers what are now Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Jordan.

With the exception of Lebanon and Syria, where we’d planned to go just before the uprising, we’ve had the good fortune to visit most of the major sites described in the book. Most recently, we spent time in Acre as did Mr. or Ms. Wetherald.

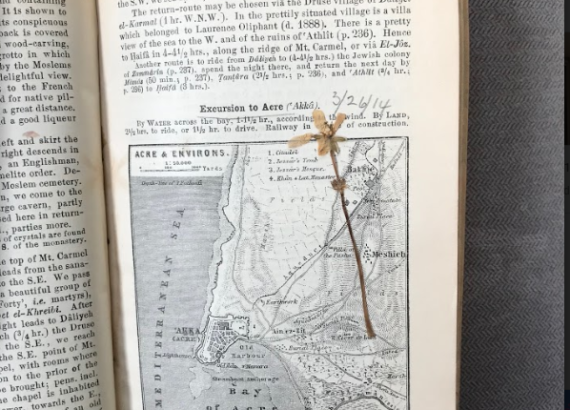

My ghostly fellow traveler must have had a special sentiment about Acre because I found a tiny dried wildflower pressed into the page containing a map of the area which has been settled since time immemorial.

It was Canaanite before waves of invaders moved in: the Phoenicians and Persians, the Greeks and Romans. It was in Acre that Herod received Emperor Augustus in 30 BC. The Roman Empire declined and other groups like the Seleucids, the Byzantines, and Ommayyad caliphs took over in a dizzying mash-up of history.

The port served as the gateway to the Holy Land during the Crusades where in 1104 the Knights of St. John conquered the city and built a gigantic castle for their headquarters. The city was popular with such travelers as St. Francis, a Holy Roman Emperor, and a king of France. Richard the Lion-Hearted saved the city from Saladin only to lose it again. The Crusader’s ever-shrinking kingdom finally came to an end in 1291. The castle was later occupied by assorted Ottoman pashas, but withstood Napoleon’s siege. It changed hands repeatedly again until 1948 when the Israeli’s took possession from the British who grabbed it in 1918, only four years after my traveler, Wetherald, visited.

My husband and I visited Acre in October. Wetherald visited March 26, 1914 according to a pencil notation. The guidebook considered Acre to be a minor excursion from Haifa, usually accomplished by boat because of the bad roads. According to the book, while the bazaar-market still presents a lively scene, the interior of the large mosque was “tasteless,” and the Ottoman military hospital “is said to have been once the residence of the Knights of St. John.”

That was then. Now the town, designated a UNESCO World Heritage site, is bustling with tourists coming to walk the picturesque old lanes, peer into caravanserais to imagine merchants off-loading their pack animals after the long trek on the Silk Road, dine by the blue sea and venture into the restored Crusader fortress, much of which is underground, dimly lit, and definitely not for those with fear of confined spaces or the dark. Our guide led us ever deeper through beautifully-restored gigantic halls that served as refectory, hospital, a storeroom for the lucrative sugar trade, and one for unfortunate prisoners.

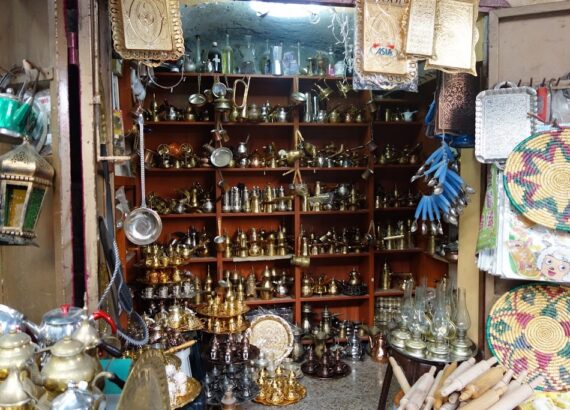

We emerged into the sun and modernity, blinking our eyes before moving into the shade of the souk. The narrow street was lined with shops filled with typical goods found in such busy markets in this part of the world: fresh fish, olives, fragrant spices, sweets, clothing, along with the inevitable buckets, brooms, and detergent.

A door at the end of the street was the entrance to what is called the Templar Tunnel where Crusaders once clanked along in their heavy armor on military business and laborers carted cones or loaves of sugar or supplies to and from the port to the castle. The tunnel is narrow and damp, and the knights must have been short because even I at just over five feet had to bend down in many sections.

We returned to brilliant sunlight at the Old Town, once one of the most important in the Eastern Mediterranean but now home to fishing and pleasure craft.

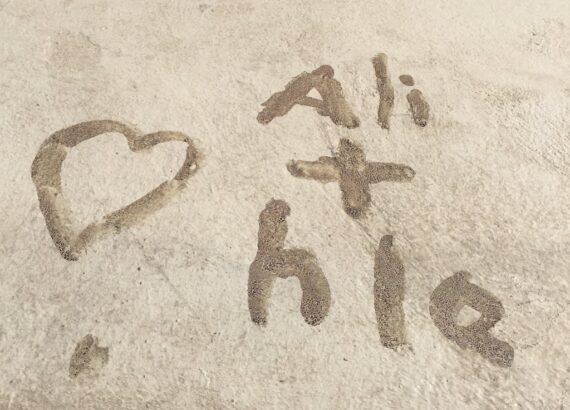

We lingered by the old sea walls watching the timeless scene and contemplating a sweet message daubed on a wall: a heart and Ali +Hlq.

And on the way back to the bus we saw more evidence of “sweet”:

***

The following day, we were presented with a graphic reminder that love doesn’t conquer all. We arrived at Caesarea to a scene combining the reality of modern times with the ancient—soldiers eyeing a display of the latest missiles.

Although the settlement was ancient, historical records begin in 22 BC, when King Herod the Great began to build up the town and port. He named it after Augustus Caesar and oversaw the construction of a temple dedicated to Augustus, a theater, a hippodrome and the famous aqueduct. The governors of Judea made it their home town when the area became a Roman province. Among the governors was the infamous Pontius Pilate. Saints Paul and Peter, among many other early Christians, resided here for various periods of time.

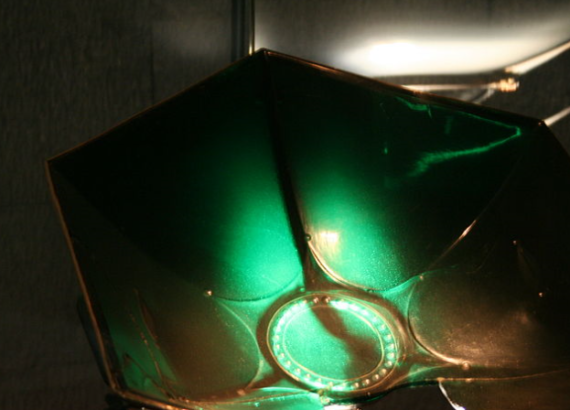

Arabs conquered the town but were pushed out by Crusaders five hundred years later. They, in turn, only hung on for twenty-one years before being swept away themselves. But one interesting side note remains: the town seems to be where the story of the Holy Grail began. When King Baldwin took the town on May 17th 1101, he seized an object from a ruined Byzantine cathedral. According to William of Tyre, the chronicler of the First Crusade, it was a round dish carved out of an enormous emerald used during the Last Supper. Baldwin was forced to give it to the Genoese in payment for the loan of a fleet. They took it to Genoa where it is displayed in the cathedral of San Lorenzo. Later, it was found to be Roman glass and is one of many contenders for the true chalice. Whatever the true story of the Grail is, the chronicler ignited the stories, legends, and quests that continue to this day.

Arabs conquered the town but were pushed out by Crusaders five hundred years later. They, in turn, only hung on for twenty-one years before being swept away themselves. But one interesting side note remains: the town seems to be where the story of the Holy Grail began. When King Baldwin took the town on May 17th 1101, he seized an object from a ruined Byzantine cathedral. According to William of Tyre, the chronicler of the First Crusade, it was a round dish carved out of an enormous emerald used during the Last Supper. Baldwin was forced to give it to the Genoese in payment for the loan of a fleet. They took it to Genoa where it is displayed in the cathedral of San Lorenzo. Later, it was found to be Roman glass and is one of many contenders for the true chalice. Whatever the true story of the Grail is, the chronicler ignited the stories, legends, and quests that continue to this day.

The city unfortunately didn’t enjoy the same notoriety and gradually sank into the sand and sea. My traveler’s guidebook didn’t think much of it, saying it was a site that could only be reached by carriage in dry weather, and if you happened to be stuck, “Bosnians have been settled here since 1884 and can supply rough nightquarters in case of need.” The book also advised that the destruction carried out after the Crusaders left was still on-going by locals needing building materials.

We walked over ancient white marble in the blazing sun, trying to imagine the scene first in Roman times when crowds cheered chariot races as in the old film “Ben Hur.”

The heat from sky and marble forced us to retreat under a palm tree for a cool drink before we trekked through a dusty parking lot to take a close look at the aqueduct, partially buried in sand. It supplied water for 1200 years but was dry by the time the Crusaders showed up.

Now, it’s a sad remnant of a once-important city, a structure that now comes from nowhere and leads nowhere, only attractive to tourists and military activity.

Another day passed in the ever-changing, never-changing, always thought-provoking Middle East. Middle-east if you live in the West, the center of the world if you’re a resident.

All photos by author except photo of “Holy Chalice” which is from Wikipedia CC, photo by Sylvain Ballet, 19 August 2009