About the only activity in the port of Seward beside off-loading luggage was that of a nearby whale disporting in the quiet sun-lit waters of Resurrection Bay. The little town, first settled in 1793 by Russian fur traders, is named for Lincoln’s Secretary of the Interior who bought Alaska from the cash-starved Russians in 1867. The port was linked to the interior by the Alaska railroad in 1903. A few years later, news of a gold strike in the interior spread to the lower 48. In 1908, surveyors rushed to map out a trail called the Seward to Nome Trail, or more familiarly The Iditarod, based on a network of existing native trails and ten thousand dreamers rushed to Seward to begin their arduous trek to the far north by dogsled. Other planned settlers never arrived after some government official came up with the idea that the town should be the site of a Jewish settlement in 1939. The plan was never implemented. World War II brought activity, and now the town is an important terminus for the cruise ships that dock there May through September. We were one of those many passengers taking a family vacation and wanting to see more of the state.

We piled on a tour bus with others from the cruise and drove along Turnagain Arm, named by the infamous Captain Bligh during Cook’s last voyage. The Arm, which goes nowhere – hence the name – has the second highest tidal movement in North America, a plus for surfers although the 1964 tsunami rushed up the Arm destroying Seward and other towns including quirky Girdwood. That town was rebuilt in a different location and looked to me like it should be the setting of a TV show like Twin Peaks. Just above the town is the Alyeska Resort, home of great skiing in winter and many summer activities, where we were to spend the afternoon and night. With twenty hours of daylight I reveled in the hotel gardens. I was leery of hiking on the many trails because it was early June, the season when bears are emerging after their long winter doze. Signs were everywhere warning visitors to be careful. We stuck together along a trail, trying to make enough noise including shaking the silly jingle bells we were given to warn the hungry animals off.

Off again in the morning we began a long day with a brief stop in Anchorage. Someone remarked that it hadn’t changed in the 30 years since she’d last been there. Indeed, it didn’t look any different than when we were there ten years ago. It was remarkable that there appeared to be no construction cranes in comparison to Seattle. Declining oil revenues have apparently brought development to a halt.

One location has changed however: the international airport has become a major hub for cargo from/to Asia. Rows of UPS, FedEx, and other cargo carriers were lined up on the tarmac or waiting to take off. Nearby, we stopped to watch the float planes, Alaska’s preferred method to reach the outback, take off and splash down from the busiest such airport in the world.

We turned north up Highway 3, the route to Fairbanks and eventually the Prudhoe Bay oil field passing Wasilla (where you cannot see Russia despite a certain politician’s claim) and Willow which hosts the official start of the Iditarod race the first Sunday in March after festivities in Anchorage.

A complicated arrangement of fencing lined both sides of the double-lane highway. The objective was to keep moose off the road but it had limited success since over 300 had been killed in collisions with cars and trucks in six months. We didn’t see any alive or dead and began to think our land-based wildlife adventure might be a bust after the wonders of the maritime part of the journey.

However, the next stop was a wildlife center centering around a tourist shop. Nothing much was in view except a couple of musk ox in a small enclosure. These curious creatures, natives of the far north, are famous for standing in a circle, young protected inside as the adults face outward with horned heads lowered against predators. We watched one trying to rub off the long winter fur against a car-wash brush; not exactly nature in the raw. The downy inner coat, called qiviut, is knitted by native women into extremely expensive beautiful hats and scarves.

We eventually turned off the main road into the wilderness to visit a sled dog kennel for a demonstration and box lunch. The dogs surprised me because they were of no particular breed in contrast to the ones we saw in Siberia who looked exactly like the UW mascot. (The puppy was adorable though). The dogs’ appearance made no difference to their desires. Like those we’d seen in Russia, they were crazy to run when the owner came out with harnesses in this case to be hitched to an ATV since there was no snow. The dogs, each chained to a dog house jumped straight up, barking furiously as if to say, “take me, me, me!” We watched them go off at a run for a few turns around a dirt track trying to envision the annual race, an 1,150-mile mid-winter race through ice-covered and snow-bound tundra and spruce forests. The Iditarod commemorates the desperate rush to bring diphtheria serum to Nome to combat an outbreak in 1925, and is now a highly competitive test for musher and dogs and a great tourist attraction. We watched a film, the theme being the great bonding of man and dog working together but oddly to me, it seemed rather defensive given challenges from animal rights activists. And I can’t help wondering what will happen as the snow diminishes because of climate change.

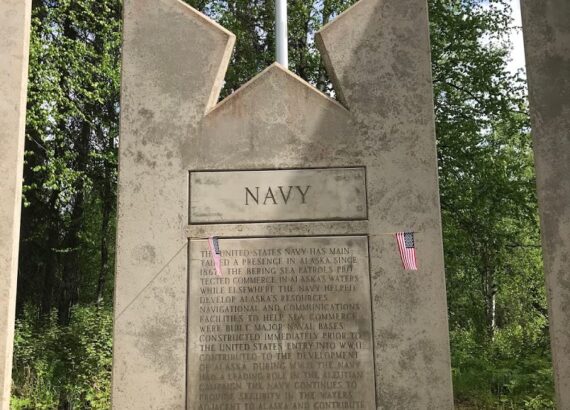

The next stop was the Alaska Veteran’s Memorial with a sculpture at the entrance honoring the 6000 Alaska Territorial Guards made up of native tribes, who were active during World War II. They served as lookouts for further Japanese incursions and otherwise aided the war effort after the Japanese invasion of the Aleutian Islands, thousands of miles northwest of the monument. The statue is set in front of a series of tall slabs, one for each branch of the military. The invasion is a little-known aspect of World War II where 1,000 US troops lost their lives along with all of the 2,000 Japanese invaders (the last by suicide). A dreadful byproduct of the invasion was the evacuation of Native Aleuts from the dry and treeless islands to the rain forest on an island near Sitka, resulting in tuberculosis and deaths. This stop was a somber way to embark on the last leg of the long bus ride.

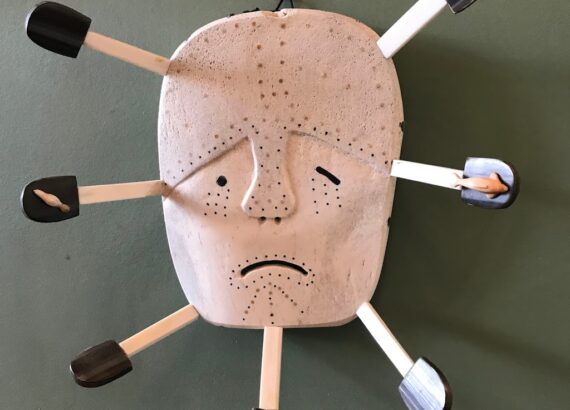

We arrived at our hotel desperate to rest our weary bottoms which had been planted in the bus for eleven hours. The accommodations at The Grand Denali weren’t especially grand but the scenery was. The food was excellent as was the interior décor in the main lodge where enigmatic Yupik masks were displayed.

The following day was filled with sightings of grizzly bears, Dall sheep, caribou, and golden eagles. Exactly what we had hoped for except no moose even though a worried-looking park ranger warned walkers to look out for an aggressive female seen in the area. Where were they? Denali wasn’t in sight either.

All ended well as travel should when we returned to Anchorage on the Alaska Railroad. Moose in abundance and the enormous cloud-wreathed mountain shining in the sun after all.

All photos except first and last (Resurrection Bay and Mt. Denali) copyright Judith Works

Resurrection Bay and Mt. Denali photos copyright Kathryn Schipper

Like this:

Like Loading...

TAGS